I’ve recently published a new update to the “Short Handbook” my father and I collaborated on. It is called How to Make Notes and Write. I’m making videos of the chapters and when that’s done I’ll probably stitch them together into an audiobook. Here are the videos I’ve made so far:

Behind the Scenes: Adding Notes

After writing my notes from the first chapter of Chomsky and Waterstone’s Consequences of Capitalism, I went through the endnotes in the Kindle version of the book I read. I followed the links to online articles, deciding to keep a few. And I made a folder in Zotero, where I stored the pdfs, web links, and citation information of books I ordered via ILL. There were also a few books which my university library already had, so I made a note of those so I could pick them up when I go in (which at this point is several times a week).

There were several really promising books cited in the notes. Maybe the main one was Gramsci’s Common Sense, by Kate Crehan. This was especially attractive because I hesitate to begin reading The Prison Notebooks right now, but I’d appreciate an explanation that covers what a Gramsci scholar considers the important highlights around the topics of cultural hegemony and common sense. There were some other provocative statements in the text that caught my eye, that referred to the writing of Paul Bairoch and Zygmunt Bauman, so I requested their books too. I also began a Research Rabbit “collection”, which allowed me to scroll through the later works tha cite some of these books. I don’t want to get too far over my skis, so I didn’t add a lot of these to the collection yet. As I read and make notes on the articles and books I’ve already queued up, I’ll add them to this collection and see what the app suggests based on that. I have a Zoom meeting scheduled for tomorrow with some of the Research Rabbit folks, so I’ll probably be able to say more if I learn more about how it works.

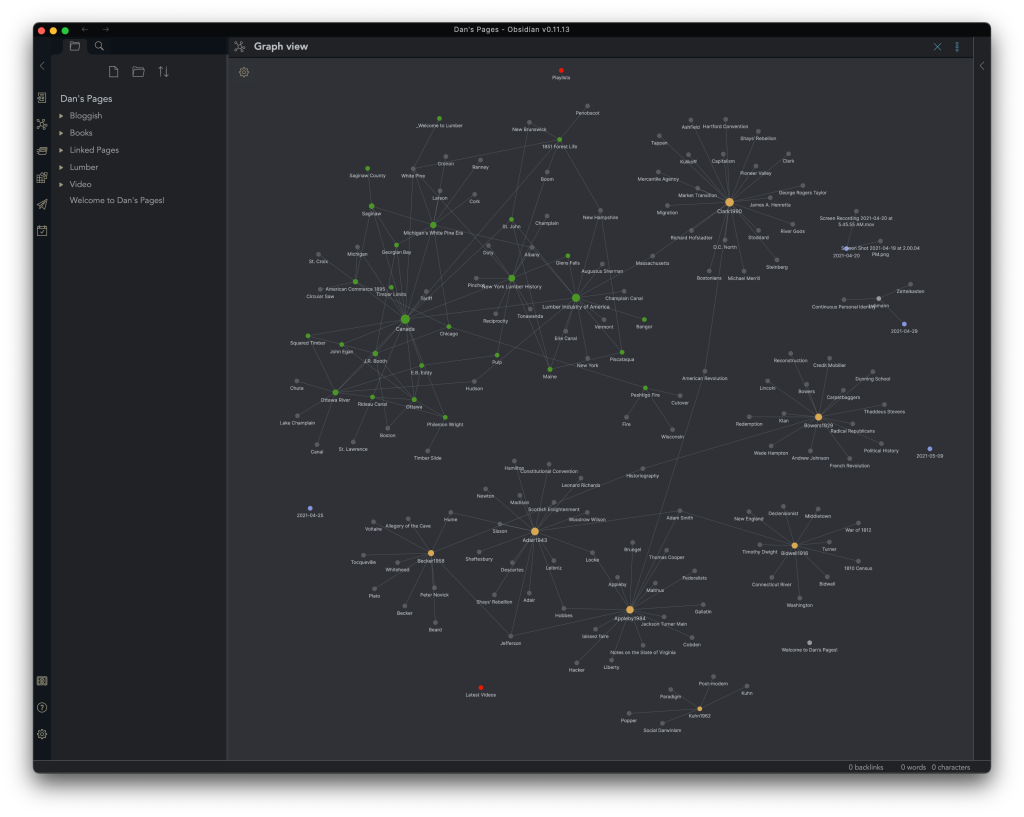

Another thing I like to do, once I’ve read a bit and written a bit, is to go back through the note and add content to links I made along the way. As I’ve mentioned, I think of the Obsidian vault as sort of a permanent work in progress. And I think returning to notes is a good way to continue pushing forward on those topics. I added some content to some of the names and terms I had double-bracketed while I was writing my notes on the Chomsky-Waterstone chapter. This is an ongoing process, and in several cases the notes I made on these terms led to new terms and notes. Some of these circle back around to the original, others don’t. Over time, the connections will become denser.

I should mention that I typically view my graph with “Exisiting Files Only” turned off. That means that around many of my nodes, I can see clusters of little purple empty notes. These are ideas, names, and terms that I think are relevant, but I haven’t taken the time to fill in yet. Over time I’ll come back to these and add content and links. For a while, I had these turned off because I felt like I was “cheating” and padding my graph if I included them. But then I decided that they provide information. A cluster of purple around a topic is a reminder that there area lot of interesting ideas there, even if I haven’t explored and reported on them all yet. OTOH, if a topic’s sattelites remain purple forever, that suggests that maybe it wasn’t really as interesting to me as I had thought, or at least it wasn’t on a “front burner”.

This isn’t meant to be a conclusive “how-to”, but rather a look at what I did in the course of working on this topic. I’ll do more of these behind the scenes videos from time to time, in addition to more formal step-by-step types of views.

Notes from Consequences of Capitalism

Consequences of Capitalism: Manufacturing Discontent and Resistance, Noam Chomsky and Marv Waterstone, 2021

Chomsky is the legendary linguist-philosopher. Waterstone is an emeritus professor in the School of Geography, Development, and Environment at the University of Arizona. He currently co-teaches the course called “What Is Politics?” with Chomsky that led to this book. Waterstone describes himself as a “Marxist Geographer” who focuses on Gramscian notions of hegemony and “common sense”.

Gramsci’s idea of Cultural Hegemony involves government with the consent of the governed. (26) So it’s preferable to military domination, but maybe that isn’t saying that much. The other concept, “Common Sense”, deals with “truths” that “need no sophistication to grasp, and no proof to accept.” (quoting Kate Crehan, who borrowed the idea from Gramsci, I think, 13) So these are ideas it is expected (or hoped) we will accept uncritically, without resistance. Things that “anyone of normal intelligence” will simply get.

Waterstone begins his first lecture with these ideas and expands them to include British sociologist Anthony Giddens’ idea of Practical Consciousness, which he distinguished from “discursive consciouness” in terms that remind me of Kahneman’s System 1 and 2. (15) Giddens also talks about what he calls Structuration, which is aprocess people use to create and reinforce their rules, but along the way they forget that these rules are artificial. They begin to believe that the status quo is inevitable, rather than contingent and human-made. Waterstone stresses (and I agree) that this blindness also helps obscure the fact that “not everyone is in an equal positiuon in making these rules and making them stick.” (16) Waterstone also cautions us that these problems are exacerbated as more and more of the information we get about the world is not from direct experience, but is mediated through media. The aculturation of common sense acts as an invisible filter of the data we are able to perceive.

One of the common sense ways we understand the world, Waterstone says, is that:

In America, if you don’t succeed, you are either not working hard enough, or you are not playing by the rules, or both. So if you don’t succeed, and this is the obverse of thinking about the American dream as it’s laid out, essentially, your failure is your own fault. This is another corollary of the individualized notion of how society works. All the opportunities are there. If you fail, it is your fault. There is nothing structural or systemic or unfair getting in your way, either historically, contemporaneously, or into the future. (23)

Some potentially useful sources on inequality might be Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickeled and Dimed or the Center for Budget Priorities’ study Born on Third Base.

Waterstone says that having “one’s view of how the world operates become predominant is a very potent form of political power. If you can convince people that your sense of how the world ought to operate is the way it ought to operate, this is an extremely powerful political tool.” (25) An important part of this is legitimacy: “The ruled must believe that the rulers are operating in their interest”. (27)

The point is that in order for there to be “fundamental social change…there needs to be cultural transformation. That is to say a new common sense, and with it a new culture that enables subalterns, that is those who are ruled or governed, to imagine another reality.” (quoting Crehan again, 29) This has generally been done to the people’s detriment, although sometimes under the claim that it was for theirt own good. In 1928, Edward Bernays said, “Propaganda is the executive arm of the invisible government.” (29) Bernays was a nephew of Freud’s whom Walter Lippmann had recruited into the Creel Commission to change the minds of the American public about participating in the Great War. In his 1928 book, Propaganda, Bernays had these things to say:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government, which is the true ruling power of our country.

We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested largely by men we have never heard of.

In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons … who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind.

Truth is mighty and must prevail. And if anybody, and any body of men believe that they have discovered a valuable truth, it is not merely their privilege, but their duty to disseminate that truth. If they realize, as they quickly must, that this spreading of truth can be done upon a large scale and effectively only by organized effort, they will make use of the press and the platform as the best means to give it wide circulation.

Propaganda becomes vicious and reprehensible only when its authors consciously and deliberately disseminate what they know to be lies, or when they aim at effects which they know to be prejudicial to the common good.

The imaginatively managed event can compete successfully with other events for attention. Newsworthy events involving people usually do not happen by accident, they are planned deliberately to accomplish a purpose to influence our ideas and actions. (32-33)

As Hannah Arendt said, in The Origins of Totalitarianism, “The result of a consistent and total substitution of lies … is not that the lie will now be accepted as truth and truth be defamed as a lie, but that the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world—and the category of truth versus falsehood is among the mental means to this end—is being destroyed”

A couple of decades after Propaganda, in “The Engineering of Consent” Bernays said freedom of speech sanctifies the right of persuasion, which allows the “media [to] provide open doors to the public mind.” Fast forward to today, when according to Waterstone, “six corporations control 90 percent of what we read, watch, or listen to.” (35) This is a dramatic change from 1983, when this percentage was spread out between fifty businesses.

Chomsky’s first-week lecture also focuses on Gramsci’s idea of hegemonic common sense. He begins with a passage from David Hume’s essay “Of the First Principles of Government” in which Hume points out that the “governed” always have “Force” on their side, so the rulers rely on managing popular opinion.

Chomsky talks about the refugee crisis at the US-Mexican border, and says many of the refugees are from Honduras, which has become the “homicide capital of the world” since a 2009 military coup that was not recognized as such by the Obama-Clinton administration because that would have required them to stop providing military aid to the ruling junta. “The US role in the flight of refugees is not secret,” Chomsky says. “It’s all public. You can easily find out about it–except on the front pages of newspapers” in the United States. (42) He then mentions the assassination of Oscar Romero in El Salvador, the 1954 CIA coup in Guatemala, and the neo-Nazi regime in Argentina (all of which he has described in greater detail in other books like Deterring Democracy).

Chomsky then turns from Hume to his friend Adam Smith, who criticized the “merchants and manufacturers” of Britain who were the “principal architects” of government policy, which they controlled to insure their interests “are most peculiarly attended to”, despite the “savage injustice” to the empire’s colonies. (46-7) Smith accused the “masters of mankind” of pursuing their “vile maxim: all for ourselves and nothing for anyone else.”

Returning to Bernays, Chomsky points out that one of his claims to fame was that he helped convince women to smoke. Then in the 1950s, he went to work for the United Fruit Company and created the cover story for the Guatemala coup, suggesting that the communists wanted to install a Soviet military base in our own backyard. In his 1947 article, “The Engineering of Consent”, Bernays said:

This phrase quite simply means the use of an engineering approach—that is, action based on thorough knowledge of the situation and on the application of scientific principles and tried practices to the task of getting people to support ideas and programs…. The engineering of consent is the very essence of the democratic process, the freedom to persuade and suggest…. A leader frequently cannot wait for the people to arrive at even general understanding … democratic leaders must play their part in … engineering consent to socially constructive goals and values…. The responsible leader, to accomplish social objectives, must therefore be constantly aware of the possibilities of subversion. He must apply his energies to mastering the operational know-how of consent engineering, and to out-maneuvering his opponents in the public interest. (50)

Chomsky says B.F. Skinner agreed in Beyond Freedom and Dignity that “Ethical control may survive in small groups, but the control of the population as a whole must be delegated to specialists—to police, priests, owners, teachers, therapists, and so on, with their specialized reinforcers and their codified contingencies.”

The term “manufacture of consent” was coined by Walter Lippmann, another progressive whom Chomsky calls a “Wilson-Roosevelt-Kennedy liberal, like Bernays”. Lippmann believed the “public must be put in its place” so that “the intelligent minorities” could benevolently direct “the trampling and roar of the bewildered herd,” the public. The role of the public was to be obedient “spectators of action,” not “participants.” (53)

This disdain for the general public was even expressed by religious leaders like liberal theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, who said that due to “the stupidity of the average man”, the “responsible intellectuals” who were their betters were forced to lead them using “necessary illusions” and “emotionally potent simplifications”. (54) These elites were sometimes opposed by “the wild men in the wings”, a term used by McGeorge Bundy in a 1968 Foreign Affairs article to describe malcontents like Chomsky.

Chomsky returns to the idea of common sense and quotes Orwell that the “sinister fact” is that censorship is “largely voluntary”. This is mainly accomplished by a good education, Chomsky says, during which “you have instilled into you the understanding that there are certain things it wouldn’t do to say, or…even to think. It all becomes part of your being. And if you’re a good student and have properly absorbed the lessons, you can become a responsible intellectual.” (57)

Chomsky also mentions that, according to John Coatsworth in the Cambridge History of the Cold War, from 1960 to 1990, there were more political prisoners, torture victims, and executions of nonviolent dissidents in Latin America than in the USSR and the eastern bloc. This is one of those facts that I really appreciate Chomsky and Waterstone citing a source for. Also interesting are the quotes from “Enlightenment” thinkers. A final one from Locke: “day labourers and tradesmen, the spinsters and dairymaids” needed to be led by the wise because “the greatest part cannot know and therefore they must believe.” (66)

Reading Notes, part 1

The thing about transferring the highlights you make into reading notes is, it can be a lot of work. Especially if you have found a good source with a lot of material in it. As excited as we may be, this could be disconcerting. Speaking from personal experience, I have found it difficult in the last several weeks, getting all my thoughts on Taleb’s book, Antifragile, into my Obsidian notes. This was NOT because I didn’t like the book. On the contrary, I liked it well enough that I quickly got and read The Black Swan, Fooled By Randomness, and Skin in the Game.

The danger for me with books of this type is that I get so excited about the ideas in them that I want to run ahead and get more. So I either read more books by the same authors or I read their sources after mining the footnotes and bibliography. I’m pretty confident that I have understood the author’s point, so it may seem less pressing to work it out in writing, which is one of the benefits of taking notes on content when you haven’t decided what you think about it. The problem is, this sense of understanding I get from immersion in the ideas of this book I’m excited about isn’t permanent.

Right now I could probably speak pretty intelligently about Antifragile, explaining both what I agree with and what I don’t using examples from the text. A couple of years from now, I’m unlikely to be able to slip right back into this same level of engagement without a substantial reread of the book. This is where my notes will be invaluable. Although there may be additional things I might notice and new insights to gain by rereading the original text, I can save the state I’m in right now with the book by taking the time to record all my notes.

This is time-consuming! I’ve just begun writing about the third section of Antifragile, and I’ve already written over 3,500 words. I don’t write this much about every book I read, but as I said, I got a lot out of this one. If these reading notes end up running over 5,000 words (which is likely), they’ll probably be the source of a bunch of permanent notes; probably way more than I typically get out of a single book. I know it will be worthwhile, but it can still be a chore getting all this down in the document.

In addition to the time this takes, there’s that additional element of being “inside” the ideas in the text right now. Although I’m writing these notes for myself, I want to remember to write them for a “me” that may have forgotten some of the details. “The sea gets deeper as you go into it”, Taleb says (paraphrasing a Venetian proverb). My goal with these notes is to be able to use them to step more or less directly from shore into the deep waters; but I need to make sure I’ll be able to swim in those waters when I jump in.

I used a lot of my downtime, waiting in airports last week, to input a big chunk of the notes for this book. I’m not done yet, so I’m going to have to allocate some more hours to this, over the coming week or so. I find that it’s kind of important to not let myself get too far ahead of my note-taking, in my reading. At a certain stage, all the content in the queue can become overwhelming.

To restate it briefly, my process is typically that I listen to an audiobook of a title that’s available in that format, and then I highlight a print or kindle copy. I listen at somewhere between 1.5 and 2.0 speed, so sometimes I listen more than once. Often I’ll run the audio again (sometimes even quicker) while I’m highlighting, just to keep me in the zone. In the past, I’ve tended to highlight only keywords so I can make notes on them when I return. Lately, I’ve begun highlighting some entire statements, if I want Readwise to find them and add them to my retrieval list (I’ll say more about this in another video). When I make my reading notes, I try to paraphrase. If I quote the author, I make sure to explain, interpret, and contextualize the quote. I’ve found that one of the most difficult things for me to understand, returning to notes after a long time away, is a naked quote that may no longer be as meaningful to me as it was when I first read it. Sometimes things are just less exciting after the initial moment, but I don’t want a valuable insight to be lost just because I failed to remind myself what it means and why it attracted my attention.

Research Rabbit Rocks!

Flipgrid and Kialo

I’ll be teaching a fully asynchronous online 8-week course this summer, on American Economic History. It’s an experimental course at a junior-senior elective level, which is also open to grad students. I have one high school teacher enrolled, who is working on his 18-credit requirement to teach CIHS classes in US History.

The basic format of the class will be that each weekly unit will include a lecture, a monograph chapter or article reading, and student responses to that content. Since this will be a fully asynchronous course, most of the interaction would normally be in writing. However, I’d like to try to improve the level of interest and increase student interaction, beyond what I’ve been able to achieve in the past with threaded discussions in the LMS or social annotation using Hypothesis. So I’m considering trying out two new apps, Flipgrid and Kialo, with this class.

Flipgrid is a free tool for creating video discussion threads. The company was established around 2015 by a UMN professor, Charles Miller, and his grad students. In 2018, the company, which had been through at least one round of venture financing, was bought by Microsoft. The upshot of that seems to have been that instead of being a fremium app, Flipgrid has become totally free for educators.

The point of Flipgrid is that I’ll be able to post video questions to my students, and they will be able to post video answers, and then comment on each other’s videos, either in text or video format. The clips will all be stored in a private “grid” and available only to invited users. So there shouldn’t be any problem with either privacy or trolls. The advantage, I think, is that in addition to the novelty, students will get to see the faces and hear the voices of people beside me. This probably isn’t quite as good as an in-person or even a Zoom discussion, but at least I’ll be able to get everybody to participate (since they’ll be graded on that), and they’ll each have to contribute to the discussion, rather than having a couple of people dominate. I’m looking forward to trying this — if it works I may even use it for some of my HyFlex or even in-person classes in the future.

The second app, Kialo, is something I had not even heard about until very recently. I think I discovered it in an episode of Sam Kary’s New Edtech Classroom. It was developed by a German-Swiss inventor named Errikos Pistos in 2017, and offers a free platform for moderated debate. The app will allow me to ask a question and have students take different sides. Pro and con arguments can be made, citing evidence from course content. And then the arguments can be voted on by the students. I think I’ll use this for a few multi-week discussion projects, on larger questions in the course. The Market Transition debate, for example, or Capitalism. I wonder whether, in addition to facilitating that sort-of point-counterpoint approach, Kialo might be used by a group to refine a shared understanding of a topic? The Kialo website includes examples not only of debates, but of preparing an essay and of what they call “Knowledge Sharing”. This could possibly be a way to engage with some of the bigger themes of the course (framing questions), over an extended period of time. I might even be able to do something with the students’ research papers in Kialo: maybe have them post their ideas for a topic and then have other students ask them questions and upvote the responses that seem interesting and promising. Kind of a crowd-sourced feedback process for their papers. Maybe I could even do exams on Kialo, which would turn them into debates or discussions and create more opportunities for students to demonstrate critical thinking, rather than just parroting info I’ve provided to them previously. That would certainly make reading exams more interesting for me!

I’ll still use Hypothesis, of course, to have students respond to individual readings throughout the term. I’m imagining these three apps, Hypothesis, Flipgrid, and Kialo, as a nested hierarchy. I may also require the students to write short reviews of the readings, which they’ll submit directly to me in the course shell. And to write a term paper. So there will still be an opportunity for them to practice the skills they traditionally learn in an upper-level history class.

New Obsidian Publish Website

Still experimenting with Obsidian Publish. I’m beginning to think this might be a reasonable way to make an all-purpose web page. I’ve been making web pages and sites, as well as blogs, for over 20 years now. Initially, I was an early adopter of the idea that everybody could embrace this new technology and speak directly to anyone who wanted to pay attention. I used to buy domains and populate them with both static pages and blogs.

I’ve let most of the domains expire. The last one that’s actually out there, live, is called environmentalhistory.us. After I finished being a grad student in the PhD program at UMass, I moved to northern Minnesota. About four years passed before I turned back to the dissertation and finished it. During that period, I taught an American Environmental History course online for UMass. I turned the content from that course into a textbook which I self-published cheaply on Amazon. That was the first text I converted to OER when I joined Minnesota State’s OER Learning Circle.

In addition to the page devoted to announcing my latest course and promoting the textbook, I also had a “Library” page that listed my reactions to books I had read, that I thought would be interesting to Env Hist students. I had gotten into the habit, as a grad student, of posting my reviews of books. And as time passed, I was a bit surprised how many visits those pages received. I suppose the readers were mostly other grad students, who had googled the book titles as part of their research. Even today, my reviews are returned on the first page of a search on most of these titles. That’s not to say I believe I had said the “last word” on any of these books. But even so, it seemed like people were interested in reading what I thought about them when I was a grad student. So I think I’ll reproduce that, only the Obsidian features of the resulting website will include the little navigation graph on the right of each page, where the reader will be able to see the links of each of the reviews to other books and to the topics I think are worth exploring.

I also had a “Primary” page which included a set of family letters from the 19th century that I later compiled into a book (The Ranney Letters). I had just added them in a blog-style long stream of posts. I don’t think this was the most effective way to make these letters available, or primary research in general, for that matter. I think the “Lumber” folder I’ve already been playing around with publishing will be a much better presentation. And since I’ll be making this available to the outside world, I think I’ll add more images. I have a LOT of scanned postcards from my trip to the Historical Society museum in Virginia, Minnesota, for example. The Virginia and Rainy Lake lumber mill there was the largest in the world in the first couple of decades of the 20th century. I didn’t see much of a point, adding a lot of images to my Obsidian vault, when it was private. Seemed to me that there might be better ways to work with those. But now that I’ll be making them public, my attitude has changed.

I’ve read and heard some folks cautioning users of Obsidian Publish to be very careful about privacy. There are certainly things that I don’t want to be out there on the public web, so I’m not just planning to publish my entire Obsidian vault. My first thought was to just take a small subset and move that content to a new folder titled “Dan’s Pages”, and only publish from that folder. I think that’s a pretty good idea, although the more I think about it, the more curious I am, how much of my actual vault is going to end up in that folder? Probably not the working folders for my OER textbooks or my Evergreen Notes (at least, not yet). And I don’t think I want to censor my Daily Notes to the extent I’d need to, in order to make them visible to the outside world. Nor do I see the need.

But I DO think I’ll expand on that idea of working with the garage door open, to include not only my white pine lumber project, but also my reading notes and a blog of sorts. Links to my videos, which may be an opportunity for me to highlight History content videos in addition to the note-taking and apps videos that are popular on this channel. I’ll be teaching a fully online, asynchronous course this summer, so there will be a series of videos that will go with that. Maybe additional things, as time goes on.

The home of all this, I think, will be my active website. Maybe at some point I’ll explore the idea of exporting from Obsidian Publish to a private domain of my own. To start, I think I’ll publish to the one I get with the subscription, which I’ll call something like Dan’s Pages, at publish.obsidian.md/danallosso. See how that works for a while.

Sources and Arguments

Sometimes people feel a sense of “writer’s block” at the beginning of a new project, but often that feeling comes from a misunderstanding. In the book How to Take Smart Notes, Sönke Ahrens criticizes writing teachers who encourage their students to “brainstorm” to come up with a topic for an essay or a research project. I think processes that include free association and a sort-of informal openness to surprising combinations of ideas can be very useful, especially in group settings. However, I tend to agree with Ahrens that if I’m doing the work of making Reading Notes and then turning them into Permanent Notes and Evergreen insights, coming up with a topic to write about ought to be the least of my concerns. The whole point of this note-taking process is not only to provide us with ideas we want to pursue, but to actually show us which ideas we are most interested in. We’ll see this process in action as we continue. Right now, let’s look a the first stage in the process: evaluating sources and highlighting ideas we find.

When you read a book, highlight, and then record your impressions and thoughts; and when you take lecture notes, you’re beginning the writing process. Yes, you’re recording information that might be on the exam. But you are also engaging with and evaluating an argument. In books, articles, and even in lectures, the author isn’t just reciting some random assortment of facts. Even if they seem very natural and spontaneous, most lectures and discussions are built around a central question or idea. If the lecturer doesn’t come right out and tell you what that is, try to figure it out. Does the syllabus give lecture titles? Are they in the form of a question? Is there a framing question at the beginning of a discussion? If it didn’t come to you in class, review your notes later and try to boil down the lecture’s or the discussion’s theme into a sentence or two. If you’re really stumped, ask.

Boiling important ideas you encounter down into a sentence or two is a key skill you’ll be learning in this process. Taking a complex narrative from literature, a textbook chapter, a primary source, or a lecture and being able to say, “This is what that was about” is a crucial step in the journey from hearing about the knowledge of others to creating your own.

As you find ideas that interest you, write them down. Review your lecture notes sometime after class (and preferably before the test!) and jot down the ideas that stood out to you. These ideas probably will be related to the point the lecturer was trying to make, but also probably will be a bit unique. Some specific things may have caught your attention, that may not be the same as the things that the person sitting next to you noticed. As long as you don’t completely ignore what the lecturer or author was trying to say, following what interests you is usually a good idea.

You’ll want to take notes when you read, too. We are going to show you a bit about how writers work: how they generally organize arguments, how they generally use setting and point of view to create atmosphere and mood; how they generally present narrators and characters to engage problems, and other similar techniques. These are valuable clues to help you determine what a text might “mean” – in general. Your task is to analyze them in the specific context of the text you are reading and interpret how they make that particular verbal contraption work. You might find once you get used to it, that such active reading doesn’t diminish, but actually increases the pleasure of reading.

On Arguments

I mentioned that one of the things you’ll be doing, as you engage with a text, is evaluating an argument. While any statement can be thought of as an argument, there is a more specific definition of the term. Under most circumstances, any deliberate statement that qualifies as a text worth engaging with is likely to have a main point that its creator is trying to make (some will also have sub-points, but they will typically serve the main point). This is the text’s argument.

Humans have been writing and reading for thousands of years, so it shouldn’t surprise you that people have been trying to work out the details of these processes for a very long time. One of the most famous writers on writing in the European ancient world was Aristotle (384-322 BCE), who was a student of Plato in Athens and later became a teacher of Alexander the Great in Macedon. Aristotle was interested in a lot of subjects, including philosophy, physics, biology, ethics, politics, geology, and logic. In his writing on rhetoric, he analyzed statements and identified some characteristics of argument that we still use today.

Aristotle found that logic was a main ingredient of many (but not all) arguments. You might recognize the logical sequence: All rabbits are mammals; Spots is a rabbit; therefore Spots is a mammal. Aristotle called this a syllogism, and he recognized it as the most powerful type of argument. You can see how it’s impossible to argue with the conclusion once you have accepted the validity of the two premises. If you can organize an argument this way, moving from agreed-on premises to an irrefutable conclusion, you’re likely to convince a lot of people.

Of course, most of the time we don’t have the advantage of being able to argue from premises that are incontrovertible facts. Sometimes our job is to show our readers new facts in order to lead them to our new, original conclusion. These can be newly-discovered ideas or they can be ideas that the reader may not have considered in the context we suggest. More often, however, what we’re really arguing about is the truth of our premises. We live in a world of uncertainty, after all. Because of this uncertainty, many of our arguments are based on premises that are tentative, leading to probable rather than absolute conclusions. Sometimes we go to great lengths to pretend our premises are certain and our conclusions irrefutable.

This may all seem ridiculously abstract. We don’t spend much time these days, dissecting or disassembling the way we think and looking at the parts. But stick with it – it’s important. When a political leader makes a claim such as “Markets should be unregulated” or “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal”, there’s usually a trail of argument behind it. If you want to understand (or especially if you want to challenge) the claim, the best place to look is at the premises that lead to the conclusion.

The form of argument we’ve been looking at above is called deduction. It builds from accepted facts to a specific conclusion. There are two other forms you should know about. Induction goes more-or-less in the opposite direction, starting with observations or evidence (like data in a scientific experiment) and ending with a general conclusion. Because in the real world we never have a chance to look at all the data, these conclusions are, by definition, tentative. But in day-to-day life we often take inductive ideas as facts. We know what’s going to happen when we throw a ball, not because we’ve studied physics and calculus, but because we’ve done it before and experienced the results. Even so, careful scientists still talk about the theory of gravity (or evolution). They don’t do this because they aren’t convinced that the theory is correct, but because there’s always the possibility that new evidence will be found that will require them to adjust or modify the theory. The point is, inductive reasoning is supposed to follow where the data leads it. But the other, equally important point, is that it’s much easier to use evidence to prove a statement is wrong than to prove it is correct. As a famous living author has recently observed (paraphrasing an even more famous dead author), you can look at white swans swimming in your lake all your life and not Prove the theory that all swans are white. You only need to see one black swan to disprove the theory, however.

Aristotle identified a third form of argument that may surprise you: narrative. Stories and anecdotes persuade us because we identify with the people and situations of the story, and because we understand the ways stories work we expect them to unfold in ways that “make sense”. A Nobel Prize-winning psychologist recently warned of “narrative fallacies”, which he describes (quoting that other recent, living author I mentioned) as “how flawed stories of the past shape our views of the world and our expectations for the future.” In fact, he said, the less actual information we have, the more compelling the narrative seems.

A famous recently-deceased historian defined history as a verbal artifact that historians use to “combine a certain amount of data, theoretical concepts for explaining these data, and a narrative structure for their presentation.” A good story can sometimes make up for sparse data or sketchy interpretation. Great storytelling sometimes can take the place of data (induction) or even agreed-on facts (deduction) in an argument. The most powerful stories can reach past the logical appeal to reason, bringing the emotions of the reader or audience into play. Fear, pride, contentment, resentment, love, and moral outrage are all powerful elements of argument, so it’s important to be able to recognize whether a writer is appealing to reason or to emotion. And then to ask why.

Also available as a video: https://youtu.be/IpeoQDoi_I4

Confirmation Bias

As I begin a series on heuristics and biases, it’s probably useful to mention that these two terms are not completely understood or accurately used by many people. Especially the term bias. When we hear the word we tend to think of “biased people”, folks with an ax to grind against some minority group. Actually, the sixteenth-century English word bias was derived from Old French or Provençal in the 13th century, and originally referred to an oblique line. So a more complete understanding of bias in thinking might deal with a tendency toward one thought, like a tilt in a lawn-bowling pitch that tends to shift the ball in a particular direction (the term was first used this way in the game of bowls in 1560). More recently, statistics has defined bias as “the difference between the expectation of a sample estimator and the true population value, which reduces the representativeness of the estimator by systematically distorting it” (Wiktionary).

In each case, the issue is a deviation from “truth”, or at least from an expected path. The ideal bowling pitch is flat, so a tilt will deflect balls from their “true” course. It might be worth noting here that this “truth” is a desired ideal rather than a measured reality. And in the sense I mentioned earlier, of “biased people”, this distinction probably applies too. We have an ideal in mind, of how we’d like to see people behave toward each other. Something that tilts that behavior, a bias, is unwelcome, often even if it operates in the positive direction because it breaks an expected symmetry. A subtle bias can be even more problematic than having a blatant ax to grind against certain people, because it’s more difficult to see and adjust for.

However, the unevenness of the bowling pitch, if it is the same for everyone, might be something we can work with, if we become aware of it. That’s part of the point of this series. Another part is because, biases and heuristics aren’t inherently bad. We don’t have them because we’re evil. We have them because they speed up our thought processes, and we evolved in a dangerous world where there was a survival advantage in thinking quickly — even if that sometimes meant making mistakes. The consequences of the two sides of a single decision are often very different. If we jump and run, and it turns out there was no tiger in the tall grass, we can laugh at ourselves (or at worst be laughed at by others). If we slow down and verify that it’s really a tiger, that verification could come in the form of being eaten.

If we look at general biases of thought, one of the most discussed today is the Confirmation Bias. This is our tendency to search for, interpret, remember, and believe information that lines up with our existing knowledge and beliefs. Again, it’s easy to imagine the evolutionary value of fitting new information into our already-formed picture of the world rather than breaking and rebuilding the whole paradigm every time we see something new. On the other hand, this can make us overconfident in our world-view, if we deliberately seek confirming evidence and avoid difficult, disconfirming “exceptions to the rule”. Inductive reasoning that operates by creating knowledge from observation can have a dangerous blind spot, if we ignore or can’t see the data that doesn’t “fit” the pattern we believe we see.

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman connects confirmation bias with memory. Associative memory is a process that searches for links between two unrelated ideas (or between a new idea and existing ones) to help us make sense of new information and integrate it into our knowledge. He observes that this process is already biased, and says this problem with “believing and unbelieving” goes all the way back tot he 17th-century philosopher Spinoza. If we are asked, “Is Sam friendly?”, Kahneman says, associative memory will immediately provide us with remembered instances of Sam being friendly. If we are asked, “Is Sam unfriendly?”, we’ll tend remember instances that confirm that description. This may seem like a trivial issue, but it has been linked to “belief perseverance”, where we tend to hang onto our beliefs even after they have been proven false, and the “primacy effect”, where we tend to believe and rely more heavily on information we obtain earlier in a process rather than later.

In today’s world, confirmation bias plays a big part in the creation of filter bubbles in social media. And in this case, the technology reinforces the most problematic part of the bias. We not only accept more easily information that already “fits” our worldview, but social media and even search algorithms have been programmed to record and catalog our worldview and then provide us with information that conforms to it and reinforces our beliefs. The algorithms aren’t doing this to be evil; they’re doing it to maximize the time people spend looking at their content because that’s how they get paid. And there are billions of dollars in play.

Since psychology suggests that confirmation bias is already strongest “for desired outcomes” regarding “emotionally charged issues”, this is especially troubling in politically-oriented social media. Over the past four years, especially, a frequent refrain in the media has been, “You’re entitled to your own interpretation, but not to your own facts.” This has typically been the response of pundits who considered themselves to have a leg up on the ignorant mobs they perceived their opponents to be. Increasingly, though, each opponent draws on a different set of facts, cherry-picked using algorithmicly-enhanced confirmation bias; resulting in each side believing the other is either completely detached from “reality”, or evil, or both.

The Greek historian of the ancient world, Thucydides (460-395 BCE), said “it is a habit of mankind to entrust to careless hope what they long for, and to use sovereign reason to thrust aside what they do not fancy.” Our easy acceptance of information which confirms and resistance to disconfirmatory counter-evidence may be the best argument for freedom of speech and an open forum for debate. If we’re hanging on to our own beliefs, even a little, then we might benefit a whole lot from talking to other folks who are also hanging onto their different worldviews.

Also a video at https://youtu.be/NpjKsbRT07o

Thinking Is Writing

“He who understands also loves, notices, sees…the more knowledge is inherent in a thing, the greater the love.” (Paracelsus 1493-1541)

“Now, a few words on looking for things. When you go looking for something specific, your chances of finding it are very bad, because of all the things in the world, you’re only looking for one of them. When you go looking for anything at all, your chances of finding it are very good, because of all the things in the world, you’re sure to find some of them.” (The Zero Effect, 1998)

We’ve already said this, but it is a key point so we’ll repeat it here. In a very real way, writing is thinking. In our experience, writing something down in a way that makes sense is how we determine that we have really understood a topic or a point. It is also the first step in making that idea our own. Although we will continue to give the originators of ideas credit with appropriate citation, when we can express an idea in our own words, it’s on the way to becoming ours.

You’ve probably often heard that the way to test your knowledge of something is to teach it to someone else. This is the same concept, but earlier in the process. There are several stages of this process and as you move through them the ideas will become progressively more your own, because you’ll be progressing from recording data to interpreting that information and making it relevant to your own interests or project.

Generally, the steps in the process are:

- Highlight a text and write a set of “Reading Notes”,

- Review your “Reading Notes” to create “Permanent Notes”.

In some cases, there may be a third step, in which you create what some people call an “Evergreen Note” which contains a distilled insight that you consider very important. This might be the type of idea that could direct a research project or become the theme or thesis of an essay.

Although it will obviously vary depending on the content you’re working with, the ratio of these types of notes will probably contract sharply as you make them your own. You can probably expect to reduce the number of Reading Notes to Permanent Notes by an order of magnitude, and then to do the same with Evergreen Notes. In other words, for every 100 Reading Notes, you may produce ten Permanent Notes and only a single Evergreen Note. This is a pretty good result, if after making note of a hundred interesting points in a text you manage to achieve an important insight. And obviously, the more Reading Notes you take, the more insights you can expect to gain.

So if the first step in creating new knowledge and then reporting on it is finding sources and learning from texts, the very first question of all might be, what is a text? For our purposes, a text is any statement you run into in written or spoken form. One of the two epigrams at the beginning came from a centuries-old book, the other from a recent movie. Many scholars in specialized fields consider images, artworks, or music to be a text that they can analyze. At the very least, in the context of a class, anything you read in a textbook, an assigned reading, a primary source, or a lecture is a text. You can take notes on what the instructor says and review those notes later. Even a discussion can be a source of valuable notes, if people have prepared their arguments. All the material you’re putting into the “mill”, grinding up, analyzing, rearranging, thinking about, and turning into new knowledge, counts.

We should be constantly looking for new information to expand our understanding, thinking about texts and analyzing them all the time. Try not to passively accept what you’re told or what you read. Ask questions, look for evidence that might corroborate or challenge claims, and compare what you’re reading or hearing with things you’ve heard before, things you’ve read, things you believe. And write your thoughts down, because, again, writing is thinking. And to be effective, we argue, thinking should be writing. We’ve probably all experienced an “Aha!” moment, when things we’ve been pondering suddenly fit together and make sense. But how often have we lost that insight, because we didn’t write it down and then forgot it. Also, trust us on this: the “Aha!” moments become more frequent and rewarding, when you’re writing stuff down.

Once you’ve discovered a text you’re going to process for its ideas, analyzing the text is the same as analyzing anything else. You take it apart so you can see what it’s supposed to do and how it does its job. Author W.H. Auden demystified both literature and criticism when he said, “Here is a verbal contraption. How does it work?”

We all learned in an English class that authors use the tools of plot, imagery, symbolism, and allusion to express ideas and values in literature. We often forget that authors of nonfiction do this too, using pretty much the same set of language tools. This is how reporters write the news and how historians tell stories. Even physicists, when they leave equations behind and try to describe their discoveries to the rest of us in plain English, find themselves using analogies, metaphors, and the other language tools we all use. We’re really doing two related things in this handbook: showing you how to analyze someone else’s writing and showing you how to write yourself. Writing an interpretive essay uses a subset of these language tools, so as you’re learning to recognize how authors do it, remember that you’re going to be doing it too.

In the next section, we’ll dig deeper into evaluating sources and taking Reading Notes.

Also a video at https://youtu.be/1mX-NoZzZ2M